The Arab Spring of 2011 has gone down in history for several reasons – and one among them is the testimony it bears to the enormous power of the internet in all aspects of life. In the consumer landscape, this is even more prominent. That the internet grants agency and power to individuals is not really a secret … but it also does so disproportionately.

That is, some internet users wield more power than others.

Think influencers.

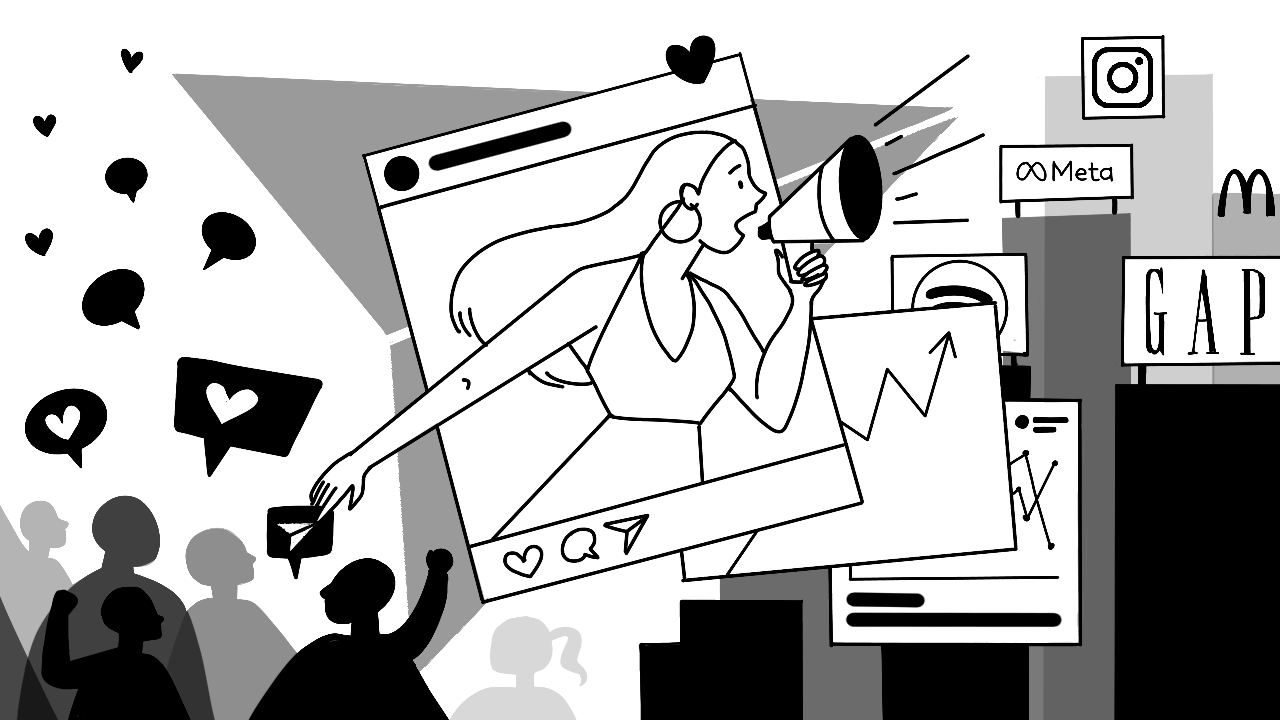

Sometime around 2018, Instagram started to blow up. Part of it was fueled by Gen-Z growing up. The slow decline of Facebook (arguably, as a result of boomers joining and a shift towards visual content) added fuel to the fire. Right around that time, brands discovered a new arsenal in their marketing strategy: influencer marketing. How exactly does one convey the essence of influencer marketing? At the heart of it, it is word-of-mouth marketing on steroids. Creators garner followers, become brands unto themselves, and wield their influence on social media platforms. Brands tap into this influence to connect to a larger audience base, and ultimately, increase their bottom line.

Influencers have been impacting consumer behaviour patterns for a while now.

Think about the last time you saw an advertisement and were tempted to splurge. What did you do next? If you’re like most of us, you probably went looking for product reviews and shopping around for opinions in your own circle of friends and acquaintances. The ad might have pulled you in, but you’re unlikely to have made an immediate purchase (and the higher the potential splurge, the truer this holds).

The reason is fairly obvious. Ads are meant to make you buy it, and are therefore inherently somewhat … “sus,” as the kids would call it. In fact, in recent years, there has been a growing impatience towards advertisements, and increasingly people are treating it like an annoyance. If you were to check your browser right now, you’d find yourself using ad-blockers at least on a platform or two. And you’re not alone. Close to 43% internet users use some sort of ad-blocker on their phones and laptops. What does this mean for brands? A tough time reaching consumers through traditional marketing channels.

Now, consider a product recommendation that comes from someone who has seemingly nothing to gain from it — like a friend. It instantly appears more genuine. This is the crux of peer-led marketing and the underlying principle that social media influencers leverage. And in a landscape where ad-blocking is proliferating and users are at increasingly liberty to turn away from and refuse to engage with commercial ads, social media influencers, this principle has also become essential for brands as a marketing strategy.

Data backs the significance of influencer recommendations when it comes to consumer demand on social media platforms. A whopping 82% internet users trust social media for guiding them on their purchase journey. In fact, the majority of Twitter users build an affinity towards a brand after it has been promoted by their favorite creator.

Why does influencer marketing work?

Trust, like we said.

Okay, but why would a teenager trust a Kylie Jenner on his Instagram more than a David Beckham on his TV?

That’s where influencer marketing trumps traditional marketing methods. The seemingly casual nature of social media helps influencers build a one-on-one rapport with their audience. Do it long enough and consistently enough, and you start building familiarity. And the more familiar we are with something, the more we trust it. And do it subconsciously.

Psychologists call it the Mere Exposure Effect.

Numerous studies have corroborated the findings of this chink in the human armor. Back in the 1920s, cultural anthropologist Grant McCracken suggested consistency as one of the key factors for successful TV advertisements. The principle was the same: when we are exposed to something consistently, we tend to grow an affinity towards it.

So influencers influence buyers to buy …?

That’s only the half of it.

All of what we’ve said so far isn’t exactly news. Influencer marketing has been around for a while now. And brands are betting big on it.

But there is something that is new – and it is still nascent and evolving. What, you ask? The subtle shift happening in the relationship between brands and influencers. Social media celebrities are no longer just influencing customer purchase journeys. They are also influencing brands’ larger business decisions.

Take the case of Instagram’s recent roll-back of their video-first strategy.

The news riled up the creator community on the social media platform. The move away from still images, and in the process, decrease the organic reach of posts didn’t go down well with most. People were up in arms. There was an online movement to force the social media giant to roll back the move. Commonplace logic would suggest that the brand would listen to the voices of dissent and respect the wishes of its creator community. But it was only after the Kardashians’ strong statements against the move that Instagram rolled back its video-first strategy.

Likewise, take the latest Kanye West-GAP controversy. The rapper’s latest fashion line for GAP used trash bags and dumpsters for promotion. The move created a social media storm, with some users calling it insensitive to homeless people. From experience, we know that when brands face mass criticism, they often roll back their campaigns, issuing blanket apologies, promising to do better. That’s the safe way out of the situation. But GAP did nothing of the sort and went ahead with the formal launch of the collection. The $300 plain black T-shirts and hoodies were displayed in trash cans at the stores for purchase.

What is happening here?

A couple of things: social capital and cancel-culture (or the flip side of it).

Social Capital

With the democratization of consumer influence, the image brand managers hope to project is irrelevant. It is now about what people are saying about your brand. And when someone with millions of followers says something about a brand, it builds perception. Why? We come back to trust.

When a Kendal Jenner takes a stand against an Instagram strategy, it has the potential to mobilize a lot more people than average users (or even micro-influencers), calling for online petitions. When fans urge Taylor Swift to boycott Spotify, they are hoping to use the pop star’s social capital to bring about a change, which, in this case, is the streaming giant cutting ties with Joe Rogan.

Social capital also has a snowball effect. There is an idea in economic theory called network momentum. Basically, shocks propagate through connected networks with a lag. It’s how smart investors are able to maximize their returns in stock markets. It works in a similar fashion on social media networks. Conversations propagate through connected networks of people, creating a ripple effect. The larger these connected networks by way of social media celebrities, the larger is the scale of the propagation.

(Flip-Side of) Cancel Culture

The network momentum theory would suggest that brands would be wary of any widespread negative opinions. Interestingly, it turns out, online calls for boycotts affect a brand only nominally. As it is, the internet itself is divided on the ethics of cancel culture. A significant percentage will continue to buy products from a brand despite controversial statements or marketing moves. This is especially true for brands that have embedded themselves in our everyday lives.

Furthermore, an increasingly polarized internet is giving rise to cliques. So, when a Kanye stands by a controversial marketing strategy, consciously or subconsciously, he is both pandering to his clique and solidifying their loyalty by garnering admiration. And strengthening his loyal fan base only furthers his social capital.

There is also the factor of divided attention spans and everybody caring about everything online. In the world of social media warriors, it is about staying relevant. When you are bombarded with new information every passing hour, there is always something else trending just around the corner. This noise gives brands a window to gamble – on what to care about or not.

Here’s our hot take.

The influence of influencers on brands – both big and small – can be considered a new and upcoming trend, seen so far only among a handful of brands with a customer base of millions.

Will other big names join the fray?

As with the internet, these things can be hard to predict. But we are betting big on the trend. Polarization of ideologies lead to stronger cliques, which lead to more polarization, which leads to … you get the idea. This feedback cycle is something that we’ve already seen played out when it comes to social and political issues. It is only reasonable to assume that the same human response will find its way to the influencer–brand conundrum as well.

But while a GAP–Kanye duo can survive social backlash because of their combined social currency and iconic presence, the same devil-may-care attitude may not favour newer players. The time is ripe for brands, especially the ones still in the process of making their mark, to assess their position and messaging, and carefully choose and chart out what kind of influencers and associations would work best for them to reach their target audience.