Remember that one time all the way back in 2013, when Jennifer Lawrence tripped and fell while making her way to the stage to accept an Oscar for her role in Silver Linings Playbook?

Embarrassing … yes, but also kind of cute, public opinion seemed to suggest. An unscripted “extra-human moment” that makes Jennifer Lawrence so Jennifer Lawrence.

Of course, if this goof-up came from a peer in our immediate circle, or ourselves, we might not have such a warm reaction. Here’s a quick exercise. Think about the last time you spilled a drink on your shirt or tripped and landed on your butt in public? Cringe. Not a pleasant memory.

Yet, Jennifer Lawrence’s fall – more than even the Oscar win – garnered instant adoration. The next year, she did it again on the red carpet, and once again, the incident was received with the utmost affection by fans across the world. Over the years, Lawrence has become as well known for her gaffes as she is for her exceptional acting talent, and people like her more for it, seeing her as down-to-earth and relatable.

So what’s going on here?

A Pratfall Effect.

pratfall (noun)

1: a fall on the buttocks

2: a humiliating mishap or blunder

In 1966, Psychologist Elliot Aronson discovered a bias phenomenon: that when people who are perceived as competent and/or successful make a mistake, their likeability goes up in the minds of the public.

In his study, Aronson recorded an actor playing a contestant answering a series of quiz questions. In one tape, the actor answered 92% of the questions correctly. Then, after the quiz had ended, he pretended to accidentally spill a cup of coffee over himself. Two versions of the tape were played to a sample of students: one with the spilling incident included and one without. When asked which contestant they found more likeable, the students picked the tape in which the contestant spills coffee.

Naturally, this intriguing psychological phenomenon at the intersection of competence, fallibility, and likeability, has been studied by various psychologists over the years. In 2002, Psychologist Joanne Silvester found something similar in job interviews: that interviewers found competent candidates who admitted past mistakes to be more appealing.

And it turns out, this bias goes beyond humans and applies to products as well. For example, cookies.

In 2015, Zenith Optimedia replicated an unpublished study by Consumer Psychologist Adam Ferrier. They asked 626 people to look at pictures of two cookies and pick the one they preferred. The cookies were the same, with one small difference: one had a rough edge while the other was smooth and round. The cookie with the rough edge was the overwhelming favourite: 66% preferred it. Clearly, the imperfection boosted the cookie’s appeal rather than taking away from it.

People, Products … what about Brands?

Let’s look at Elon Musk’s 2019 Cybertruck bungle. When Tesla unveiled the vehicle, Musk declared that the electric pickup truck was virtually bulletproof. To demonstrate this, Chief Designer Franz von Holzhausen threw a steel ball at the prototype’s windows … and they cracked immediately on impact.

A PR nightmare, by all measures.

Yet, the incident did not dent Tesla’s or Musk’s reputation. If anything, it was perceived meme-worthy and humorous rather than a concerning sign of the quality of the product. Musk himself embraced the hilarity of the incident, taking control of the narrative and even selling T-shirts about it. Eventually, the incident translated into more traction and over 250,000 reservations for the Cybertruck. A brilliant example of a brand turning around an evident flaw in its favour.

Is there a marketing implication?

So far, we’ve looked at inadvertent mistakes that have either organically boosted someone’s popularity. Or accidents that have been exploited to stoke brand image after the fact.

But can the Pratfall Effect be consciously leveraged as a marketing strategy to boost your brand’s image and position in the market? Can ad campaigns that focus on a flaw actually work?

The answer is yes.

And some brands have done it before with great success.

In 1968, when Volkswagen launched its Beetle, the company was acutely aware of its shortcoming: the car was simply too small. Since this is not something that can be hidden behind clever marketing copies, Volkswagen did what few would dare to. They decided to highlight this perceived imperfection to garner intrigue. Not only was the public response overwhelmingly positive, but the Beetle also went on to become an iconic model, well-sold model.

So why does this work?

The intuitive understanding, of course, is that admitting weaknesses makes people and brands more relatable and sincere. Especially in an age when authenticity is a valued concept.

But there’s more to it, especially when it comes to brands.

- Controlling the Narrative

It is almost universally accepted and understood that brands (like people) are fallible. No one expects a company to never make a mistake, or be 100% on point all the time. So, when a brand does its utmost best to put out a perfect, error-free image, it comes across as impossible, and therefore, insincere.

Imagine you want to purchase something. You go online and look through the product reviews. All you find are overwhelmingly positive reviews with not a single criticism. Does it reassure you? More likely than not, it will give you pause – and not a good one. Did the company buy fake reviews? Were the critical reviews expunged? In 2015, a study by Northwestern University proved just this. It found that likelihood of a potential buyer purchasing a product “increased as the average review rating went up” but only until it reached 4.2–4.4 out of 5. After that point, as the rating went up, the likelihood of purchases dropped significantly.

Contrary to this, if a brand is open about its flaws, it can control the narrative around its credibility. It can show consumers that its flaws – inevitable as they are – lie in inconsequential areas. For example, consider a budget hotel that openly advertises low rates for excellent rooms at the cost of slightly compromised service, such as no complementary meals or no bell-boy service. By admitting what it does not offer, the brand can reassure the consumer about the source of the cost-cutting – and by extension, that the low rates don’t come at the cost of comfort, cleanliness, or safety.

- Establishing Credibility

When a brand admits a flaw that is publicly confirmed, it is a tangible demonstration of authenticity and honesty. In doing this, the brand is establishing itself as believable, since clearly, no one will lie about a flaw. Now, our minds tend to default to appeal to authority – considered a fallacy by logicians and a common component of human psyche by psychologists. This means that most people perceive established credibility in some areas as proof of credibility in other areas.

For brands, what this means is that once a positive image has been created in terms of its honesty (in this case, about shortcomings), other claims automatically become more believable. Thus, admitting flaws can be used as a strategy to increase a brand’s credibility quotient.

But … before you put out that ad declaring your mistakes…

While the Pratfall Effect can be a useful tool in a marketer’s toolkit, it also comes with certain risks if not done with utmost care. This is not a strategy you want backfiring.

So here are some caveats to keep in mind.

- Only pratfall from a position of strength.

There’s a common thread running through most studies and incidents where the Pratfall Effect comes to play. What’s that? Competence. For the bias to work in a brand’s favour, the brand must already be perceived as competent and credible – good at what they do. If the Cybertruck incident happened with a less well-established company than Tesla, without the involvement of a figure as mighty as Musk, it might well have spelled the end of the brand’s reputation. Indeed, Aronson’s original study showed that Pratfall Effect only sets in when the contestant was perceived intelligent and capable. The same spilling incident did not garner likeability when done by a contestant who could only answer around 30% of the questions correctly.

Recall the many Trump tweet fiascos from 2017, for instance. Since the media already had a low opinion of the former US President, these tweets did nothing to improve his image. In fact, the incidents further fueled people’s suspicion over his ability to lead a nation and resulted in widespread mockery.

Thus, the Pratfall Effect can be leveraged only once you’ve already established your brand and its trustworthiness, and not a minute before that.

- Understand the difference between flaws and fiascos.

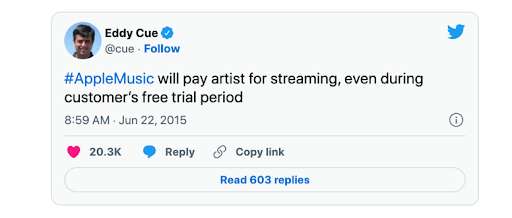

Honesty is an excellent trait for brands, but how much honesty is too much honesty? Flaunt your flaws, as we said. Small mistakes, goof-ups, weaknesses that bely imperfection but sincerity. Like when Apple admitted its fault and apologized, in response to Taylor Swift announcing a public boycott of Apple Music. The mistake? Offering a 1-month free trial of its streaming feature (this is good) but not paying artists for any of the music played during the trial (this is not). Apple SVP of Internet Software and Services Eddy Cue took to Twitter to humbly right their wrong.

But the Pratfall Effect does not extend to messy, serious errors that have strong and/or devastating real-world consequences. Or shortcomings that straight up declare your brand as incompetent, incapable, or inefficient. For example, there is nothing endearing about a car company whose cars have to be recalled due to safety failures. While a mistake must still be acknowledged and rectified, this is not one to flaunt.

That is to say, always consider the consequences and gravity of the flaws that you decide to wear on your sleeve and leverage as a marketing strategy.

Our takeaway?

Overall, Pratfall Effect is an excellent marketing strategy – a counterintuitive yet effective way of building customer trust and a positive image of your brand as authentic. But it must be done just right … because the slightest miscalculation can blow up and backfire.

If you decide to test out the strategy, we recommend leaving it to the experts. So you don’t land yourself into a covfefe-esque mess.